Teaching guides

Effective Feedback Ideas with Cadmus

Share with colleagues

Feedback is an essential part of the assessment process, supporting student satisfaction and improving learning (Hattie and Timperley, 2007). We know that effective feedback is timely, giving students an understanding of where they are at, and where they can go—but what does this mean in practice?

When you design your assessment, you also design your opportunities for providing feedback. Making smart decisions about when and how you'd like to provide feedback, can make a world of difference to the way your students engage and perform. It's best to invest your time giving detailed feedback while students still have the opportunity to improve—be that on a draft submission, or early assessments in a series of tasks. That is, to really impact student learning, it's best to deliver formative feedback.

But wait, I don't have time to give more feedback

Before we dive in, it's important to address one of the biggest challenges when it comes to giving feedback. We all want to do more of it, but do we really have the time? We often imagine giving formative feedback as reading pages of drafts for hours and then marking them up with detailed comments. In reality, there are plenty of other methods for giving feedback that are less intensive and empower students to take ownership of their learning.

Teachers that put in the extra effort to give feedback during an assessment noticed that the time spent early on in the assessment process often saved them time later on.

Receiving feedback helped students understand the assessment criteria earlier, which increased their satisfaction with the teaching environment. This also saved teachers time, as students were less likely to seek clarification about their performance after grades were released—when it was too late to improve.

Feedback ideas

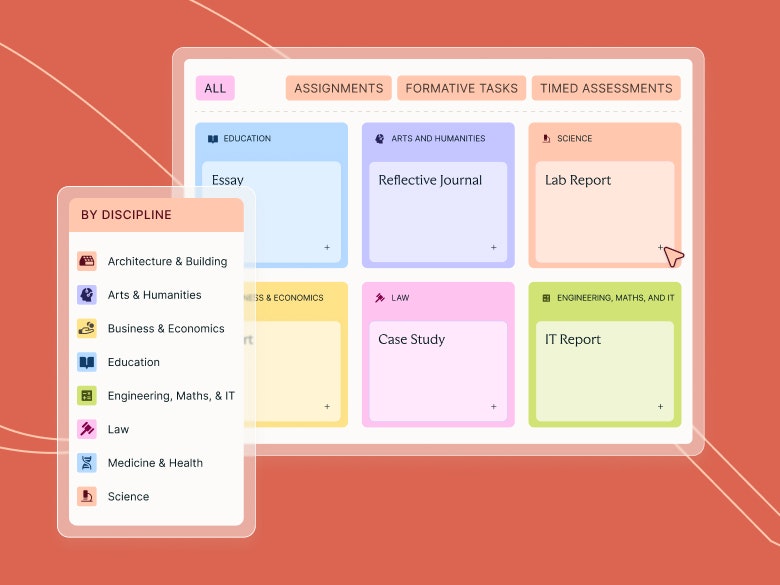

In this guide, we'll focus on ways to deliver feedback while students still have the ability to revise their work. Many of these ideas can still be applied to summative assessments or combined with summative feedback processes. These strategies involve varying levels of effort, impact and outcomes—giving you the flexibility to align a feedback process with what works best for you and your students.

Rubrics and grading criteria

One of the best ways to achieve consistency and efficiency in your assessment feedback is to use a rubric. Rubrics are valuable in communicating assessment expectations to students and can save you from making repetitive comments on student work. They're also a powerful teaching tool, helping students develop the ability to continuously self-assess their work.

If there's only one thing you do to improve your feedback processes, make it using a rubric.

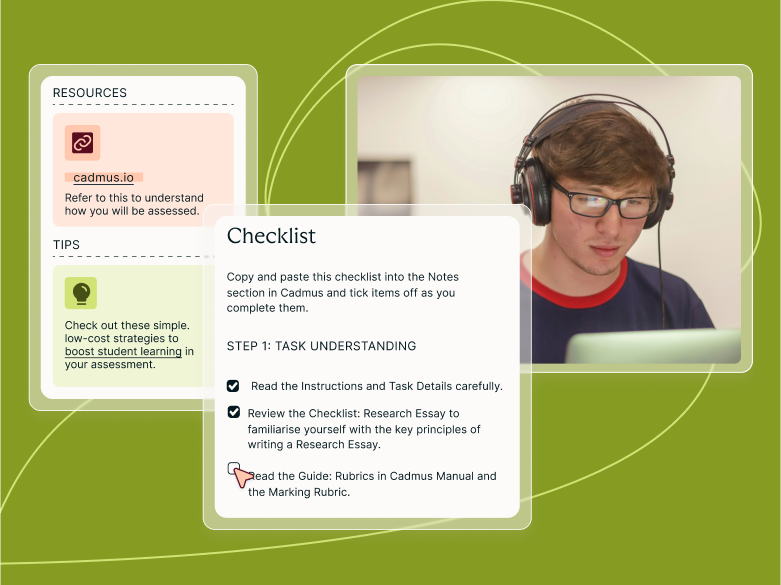

Developing a rubric requires a bit of work during the assessment design stage, but there are plenty of great resources and templates you can use online (try UNSW Teaching and Berkley Learning & Teaching). Once you've created a rubric, you can attach it as a resource to your Cadmus Assignment. This means your students can access it from the very beginning, and you can continue encouraging students to engage with it throughout the assessment.

Individual feedback

If you want to give students the best feedback and assessment experience, you can't look past providing students with individualised feedback. With personalised feedback, students are aware of specific opportunities for development and often feel higher levels of satisfaction with the teaching environment. However, with individual feedback being the highest cost, it's important to look for small ways to speed up processes.

Remember: Cadmus is integrated with Turnitin, which means you can use a lot of the functionality in Turnitin Feedback Studio to improve your marking workflow.

Here are a few ways you can deliver individual student feedback:

- Provide detailed comments on student work.

- Assess work against the rubric. Link each standards descriptor to actions students can take to improve within a criterion.

- Write up a collection of common feedback, and use a key to assign feedback to student work quickly.

- Use QuickMarks in Feedback Studio to create a bank of frequent comments you can quickly add to assessments.

- Create a Turnitin rubric to speed up grading and calculating marks.

- Try using audio recordings for detailed student feedback—you can do this directly within Feedback Studio.

Group feedback

For larger classes, giving detailed individual feedback may not be feasible. Group feedback can become a good option instead. After reading a selection of submissions in Cadmus, you can provide feedback to the cohort on common issues that you see. This could be as a short video, during a lecture, or written up as a document. You can also share relevant resources to support students, or consider addressing any major issues with learning activities that develop skills and knowledge gaps.

Tip: Combine this with your experience running the assessment with previous cohorts. Share tips and answers to frequently asked question that you have had from students in the past.

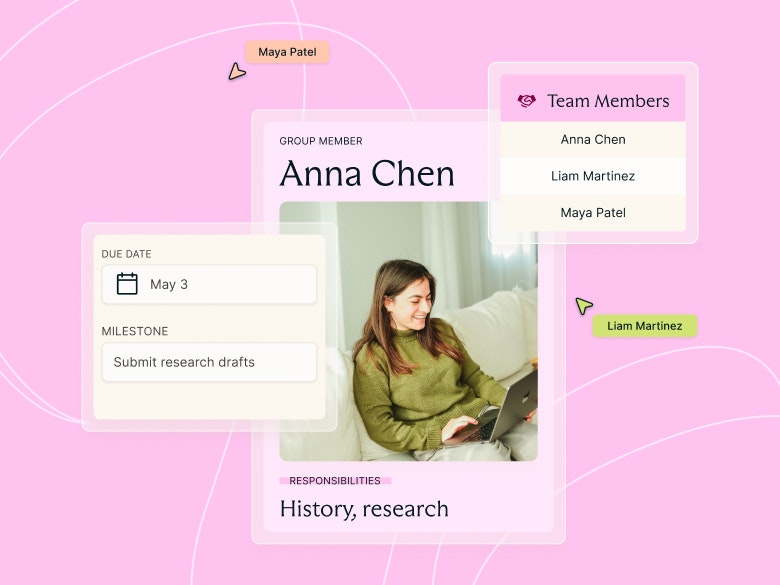

If you're working with a team of tutors, get them involved as well. Tutors can review their own class's work and then present feedback during a tutorial. Using class time to run activities to develop a specific skill can be highly effective in delivering targeted feedback. Students can then act on their feedback in class, or continue developing their work in their own time.

Peer review

There is a shift in current feedback practices to supporting students in generating and soliciting their own feedback (Boud and Molloy, 2013). Peer review is one way we can achieve this, having a range of benefits (Carless and Boud, 2018). There is less pressure on teachers to review all the submissions, students receive individual feedback, and students develop their own evaluative skills (did someone say win, win, win?).

You can conduct peer review as an in-class activity, or a structured, separate assessment. Begin by introducing students to the rubric, so they form a clear understanding of assessment expectations. You can then talk students through the evaluation of an exemplar, helping them understand how to identify key criteria and the appropriate standards descriptors for a piece of work. This can then be followed up by an exercise where students provide feedback on a peer's work, explaining why they believe the work meets the identified standard.

Tip: You can download students' draft submissions from Cadmus as .pdf's and share them within the class. Or ask students to send the PDF copy of their work to their classmate—they'll find it attached to their submission receipt email from Cadmus.

As a next step, you can identify common feedback that students receive, and guide a discussion on ways to improve specific aspects of the work. A similar peer review exercise can also be completed by asking students to submit a short write up of feedback through Cadmus, which you can use to draw out shared concerns.

Self evaluation

Empowering students to develop their own skills, and become self-directed learners is another effective method for enabling feedback delivery (Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick, 2006). Instead of investing time into providing individual feedback, you can spend time equipping students with the skills required to make judgements about the quality of their work.

This can be achieved through a series of learning activities, similar to those used for preparing students for peer review. Guide students through the process of engaging with the rubric, evaluating exemplars, and then evaluating their own work—before asking them to submit a written self-assessment that identifies areas where they still need more guidance.

By asking students to self-report on areas they have identified as "needing more work", you can ensure you are providing targeted feedback, not just generic suggestions.

With this approach, you'll be spending the majority of your effort on communicating strategies for improvement, not identifying areas of weakness. This means you can devote your time to actions where you have the greatest expertise, and students require the most assistance.

With a greater understanding of options for delivering feedback, you can pick and choose from different strategies to suit individual assessments. What makes sense for one task won't always work for another, so it's important to be flexible and stay open to trying new methods.

Category

Hybrid Learning

Student Success