Teaching guides

Principles of Good Feedback

Share with colleagues

Feedback is vital to student learning, and an important part of how students develop within an assessment. As we spend time developing our understanding of best-practice assessment, we also need to understand the power of feedback and the role it plays in enhancing the student experience (Hattie and Timperley, 2007).

Formative feedback

When we talk about feedback, we often refer to formative feedback—that is, feedback designed to support student learning. It occurs during the learning process, so students still have the opportunity to act on it and improve. Students develop their skills and understanding through doing and making mistakes (Naylor et al., 2014), which makes formative feedback the guidance they need to course-correct and progress.

In contrast to this, we have summative feedback (think grades or exam marks), which makes final judgements on student learning. Summative assessments are a necessary part of the educational experience; however, to fully benefit students, they should be accompanied by formative feedback (Biggs and Tang, 2011). By shifting our view of assessments from evaluations of student abilities to opportunities for student learning, we will naturally find ourselves embedding more learning and feedback opportunities into our teaching.

What makes feedback effective?

There are no hard and fast rules for how you should be delivering feedback; the importance lies in understanding your learning outcomes and what you want students to achieve in any given assessment. Within this scope, there are a few fundamental principles we can follow which enable constructive feedback delivery (Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick, 2006).

Feedback is timely

The timeliness of feedback directly influences a students ability to reflect on their work, action the feedback, and improve; so it's important to consider when you want to give feedback. The smaller the window between receiving feedback and acting upon it, the more likely it is that students will learn and engage.

That's why you'll find that detailed comments given at the end of a major assessment will most probably be forgotten, but targeted feedback on a draft will significantly improve a final submission. By front-loading feedback in this way, earlier learnings can influence later work appropriately.

Tip: If your students are working on a major assessment, ensure they have plenty of opportunities early on to clarify their understanding and processes.

Feedback helps clarify what good performance is

If we want students to understand and be receptive of feedback, we need to communicate expectations and standards appropriately. The best way we can consistently do this is by using rubrics or grading criteria. Using criteria with clear descriptors helps students frame up any feedback they receive, identifying where they are at, and what higher levels of performance look like.

Tip: Exemplars are another resource you can use as a reference for quality work. Talk to examples as a way of contextualising and reiterating your feedback.

With evidence suggesting students don't always know how to interpret feedback (Naylor et al., 2014), there's plenty of work we can do to encourage students to engage with criteria regularly throughout an assessment. Consider embedding these resources into the delivery of your assessment and relevant learning activities.

Feedback provides a way forward

For students to get value from feedback, it should be targeted and tied to specific learning goals. By using rubrics and criteria, you can help keep this principle in check, linking comments to particular skills or performance indicators. More than this, the information provided to students should also go beyond identifying strengths and weaknesses in student performance.

Effective feedback should help students answer the question, where to from here?

By providing corrective advice, students feel equipped to make necessary improvements to their work. Similarly, the level at which this advice is given impacts how students learn and progress. Feedback can be provided concerning performance on a specific task, a student's process of completing a task, or a student's self-evaluative processes (Hattie and Timperley, 2007).

Feedback level examples Task level Remember that you need to discuss demographic factors like gender and age when analysing the data. Process level You can try referring to a range of sources, including those that support opposing claims. Try unpacking the motivations of authors on both sides of the argument. Self-regulation level Given you have access to the marking criteria, try assessing where you think you sit for each criterion. Look for areas you can work on, and how you can manage your time to develop these.

Feedback helps students develop self-assessment skills

Feedback has evolved to become more than just information sharing from teacher to student. Effective feedback seeks to equip students with the skills they need to make sense of their own work and make appropriate judgements (Carless, Boud 2018). The work you do here may not explicitly feel like giving feedback in the way you are used to, but it becomes valuable in helping students become self-directed learners (Ambrose et al. 2010).

Part of this involves setting realistic expectations around feedback engagement outside of university. For example, students need to know that they will need to be comfortable with proactively seeking out feedback independently in the workforce.

Once students see the value in generating feedback themselves, they no longer see teachers as the only feedback source they have.

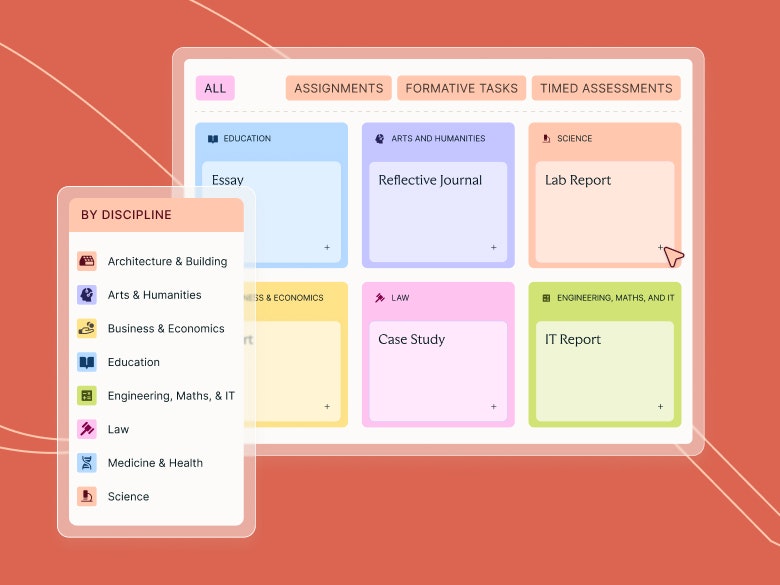

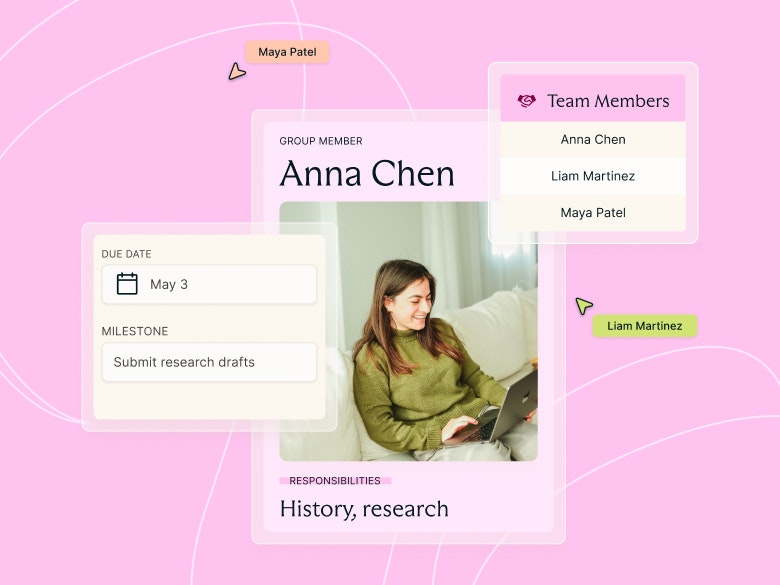

Outside of themselves, peers, Turnitin and even educative scaffolds in Cadmus all become examples of feedback channels for students. It then becomes the role of educators to create opportunities for students to practice self-evaluation skills and leverage the sources of feedback at their disposal. These skills need to be explicitly taught to students early on so they can develop feedback literacy (Carless, Boud 2018).

By keeping these principles in mind as you design your assessments and feedback processes, you can enhance the way your students engage with feedback. For more ideas on how you can put these principles into practice, check out our feedback ideas guide.

Category

Hybrid Learning

Student Success