Teaching guides

What is 'Best Practice' Assessment?

Share with colleagues

As teachers wanting to improve assessment practices, we're always working towards a gold standard. At Cadmus, we use the term "best practice" to describe this goal. We've developed this understanding through engaging with teaching and learning research, industry policies, and the experiences of academics and students. So before we encourage you to follow best practice in your assessments, let's take a look at what it really means.

It's all about learning

We know that students learn through what they do, which usually involves preparing for and completing assessments (Bearman et al., 2014). If a student's experience at university is to be centred around learning, it only follows then, that assessments should be used to promote learning.

Whether you call it assessment for learning, learning-centred, formative, or best practice; when we design assessments, we are designing what and how students learn.

So how does learning work?

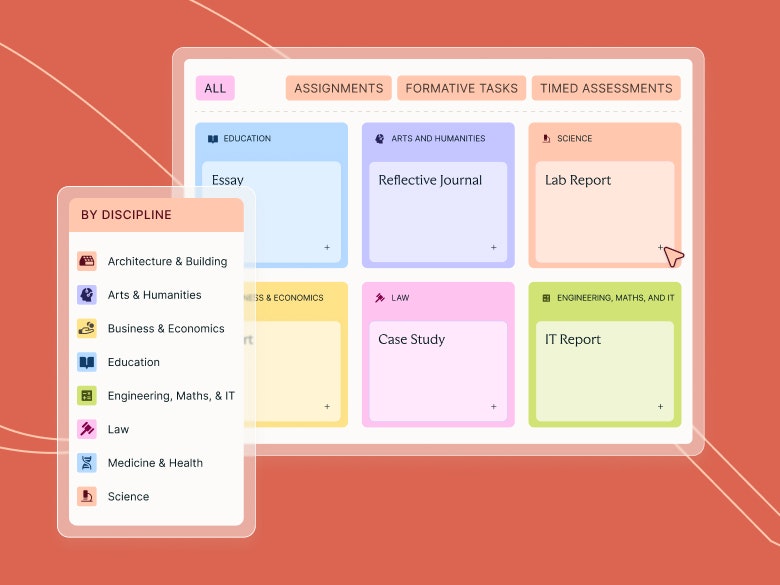

How Learning Works by Ambrose et al. (2010), outlines seven principles that foster student learning. These principles take a holistic view of learning, considering the impact of student attitudes, their skills, and their environments, on learning. By embedding these into the way we design and deliver assessments, we can improve the way we facilitate student learning. At Cadmus, these principles help us make decisions that shape product features, assignment templates, and educational resources.

Let's take a look at these principles, and how they can inform the assessment decisions we make.

Motivation affects how students learn

Motivation is arguably the most important factor in student learning. Without it, we see students disengaging; closing themselves off from the actions necessary for learning. However, when present, students have the potential to maximise their learning, experiencing enjoyment while doing so. Student motivation is highest when they can identify a valuable goal to achieve and can foresee positive outcomes.

Remember: Students' goals aren't always the same as our own, so finding common ground is key. Take time to understand what your students care about.

Moreover, students need to feel confident they can achieve these outcomes, based on a belief in their own abilities and skills. The learning environment also plays a role in impacting student learning behaviour. When students feel supported by the environment (be that from relationships with teachers, through resources, university services, or their peers) they experience higher levels of motivation. When they perceive a lack of support, however, they can disengage at the first sign of difficulty.

For example, a student studying biology needs to believe that writing a lab report will develop valuable communication skills necessary for a successful career in the sciences. They also need to believe they have adequate skills and support to successfully write the lab report.

To motivate students in their learning, assessments should:

- Be well aligned with learning outcomes and learning activities (Biggs and Tang, 2011). Students lose motivation when they are assessed on things they have not learnt, or learn things they are not assessed on. This is a result of poor alignment.

- Outline the purpose of the task, what needs to be learnt, and how it is relevant to students’ lives.

- Be authentic and reflect real-world tasks. Student goals often link to life beyond university or studying.

- Set clear expectations and paths of attainment for completing a task. Rubrics and checklists can support the communication of this.

- Present low-stakes opportunities early on for students to experience success. This can boost motivation and increase students' confidence in their own abilities.

Prior knowledge impacts future learning

Existing knowledge influences how students filter and interpret what they learn, either helping or hindering depending on the accuracy of the knowledge. When students learn new concepts by drawing on existing knowledge, they may not understand the applicability or relevance of their knowledge to the current topic of work. Gaps in knowledge or even inaccurate prior knowledge can set students off on the wrong path.

With classes made up of students from diverse backgrounds (high school leavers, mature age, international students, etc.), all with varying degrees of knowledge, it can be a challenge to know how to provide assistance. Especially in first-year or pathway classes, teachers should aim to become aware of students' skill levels (and avoid making assumptions), in order to provide wide-reaching support to students.

To make sure that we support all students in their learning, assessment should:

- state expected prior knowledge and how this connects to new learnings, both in terms of content and skills

- review prior skills and explain how they can be appropriately applied to the task

- incorporate learning activities and learning resources (ie. guides and feedback) to support the varying levels of understanding, or to address any misunderstandings

- provide students with guided processes to follow as they develop new knowledge and skills.

Students need guidance organising their knowledge

As students learn, they connect pieces of information to form knowledge structures. When future learning occurs, this knowledge is then accessed and applied. When these structures are meaningfully organised and accurate, learning becomes more effective. This can help students shift away from learning facts for recall, and towards connecting more complex ideas and themes that can be applied to new situations. These deeper connections allow skills to become embedded into students' natural ways of thinking and working in the long run.

This doesn't just apply to discipline knowledge; the same principles can be applied to the development of academic skills. If students practice the skill of citing within the context of research and note-taking—not as an isolated task when writing assignments—they can embed better academic writing practices into the way they work, and understand the value of academic integrity.

To help students structure their learning and knowledge, assessment should:

- connect the knowledge of a single task to other learnings, the course, and the real world

- provide students with frameworks to organise their own information, helping them develop high-level thinking skills

- outline the steps in a learning process to complete a task

- state when certain pieces of information are most relevant and should be engaged with.

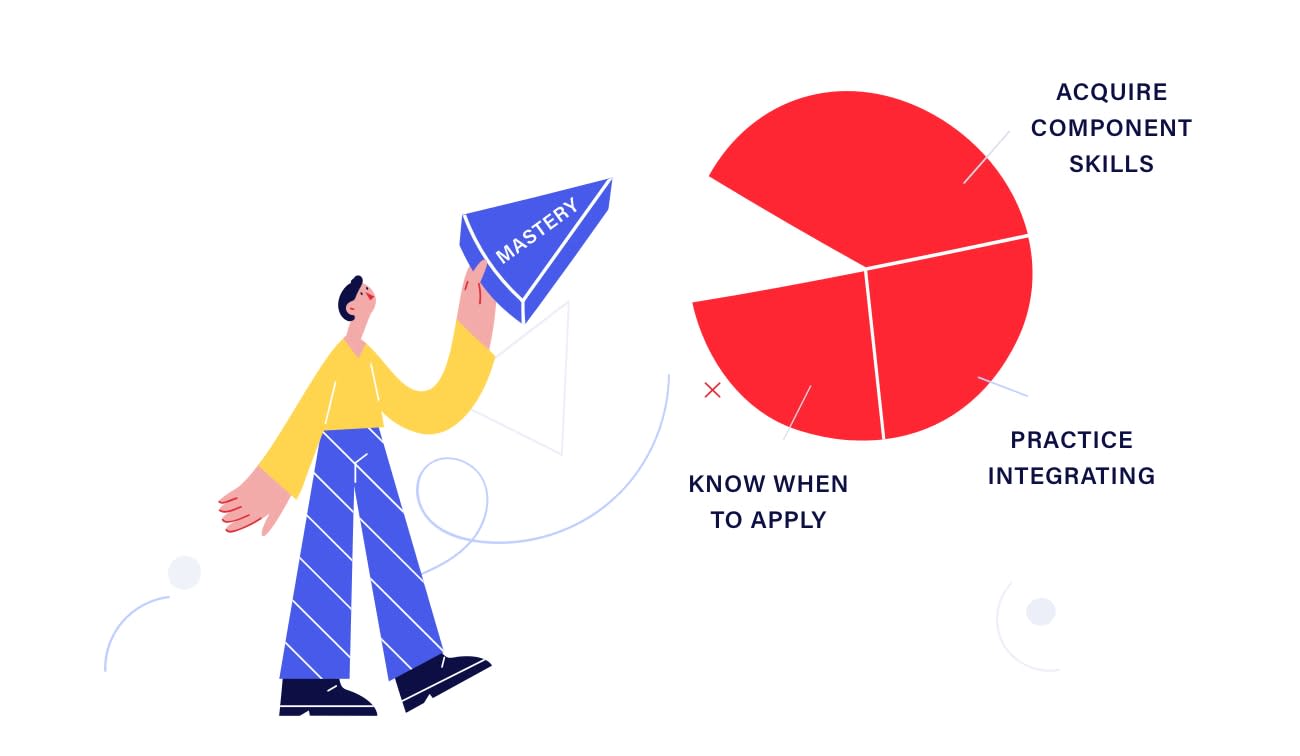

Students must learn component skills, how to integrate them, and when to apply them

In developing mastery, students must acquire not only the necessary component skills and knowledge, but also an understanding of when and how to apply these skills. Many academic skills or graduate outcomes are made up of component skills. When students don't have a proper grasp of component skills, they can struggle to successfully complete larger tasks.

For example: A student asked to critically analyse the weekly readings needs to develop component skills such as identifying arguments, understanding context and finding similarities or differences with other texts, just to name a few.

Once these individual skills have been acquired, students should practice integrating these skills in more complex tasks. Along with this, students should also learn when to apply skills. We can encourage students to apply existing skills in different contexts, and explicitly identify connections between skills and applications. With exposure to different contexts, students can develop greater fluency, becoming more confident and intuitive in their application of skills.

To help students develop mastery of skills, assessments should:

- break complex tasks down into component parts, providing students with sufficient opportunities to develop component skills

- identify missing or weak component skills, and focus on developing these further

- clearly explain how students can learn and develop new skills, as well as apply existing skills

- consistently build on skills in subsequent and connected tasks

- outline when and how these skills can be applied in real-world settings and in other assessment tasks and learning.

Students need targeted practice and targeted feedback

Learning is best supported when students have a specific focus and target criteria. This means assessments should be designed to evaluate well-articulated learning outcomes. With a clear goal, students then need sufficient opportunities to practice skills and develop knowledge. When this is connected to effective feedback strategies, students find themselves in a cycle of practice, observation and feedback, eventually leading to mastery of skills and knowledge.

This requires feedback to be directly linked to specific target criteria, and also be delivered at a point in time that allows for further practice opportunities. It is important to consider the burden on educators in delivering consistent feedback, and instead find efficient ways to create low-cost feedback opportunities.

To enable this process, assessments should:

- identify specific learning outcomes to be assessed

- use rubrics to support the communication of expectations

- set expectations about the standards for practice or work required

- include examples of work that meet the performance criteria

- include multiple points within the assessment process for feedback.

Student development and course climate impact learning

Student development includes individual and intellectual development. That is, a student's ability to appreciate nuance in what they learn (not just right and wrong), as well as their ability to develop individual opinions in the context of their learning and the wider world. While teachers can't control student development—only encourage it—we can be conscious of where students are at in their personal learning journeys.

Course climate, which takes a broader look at the learning environment, is an area where teachers have more control. It includes the intellectual, social, emotional, and physical environments in which students learn. It is influenced by a range of factors, but in the context of assessment, interactions between teachers and students become important.

A positive tone set within a subject should flow down to individual assessments, helping students feel comfortable within the learning environment.

To support a positive learning experience, assessments should:

- support students as much as possible in their learning

- echo the tone of the learning environment, encouraging students to seek help and engage in discussion

- make students feel comfortable sharing their own opinions and views in their work

- use inclusive language and examples (consider non-native English speakers and cross-cultural contexts).

Students must learn the skills necessary to become self-directed learners

Ultimately as teachers, we want students to become lifelong learners, aware of their own learning processes. This enables students to direct their own learning and equips them with the necessary skills to take on complex tasks post-university. To do this, students need to be able to monitor and control their own performance. This process—which involves assessing the task at hand, evaluating personal strengths and weaknesses, planning an approach, applying strategies, and finally reflecting on the experience—needs consistent support and guidance to develop.

Teachers often assume students have already developed many of these skills, as they become second-nature to educators over time. However, unless these skills have been taught and developed previously, students rarely possess them and are not explicitly aware that they are valuable.

To support students learn self-directed processes, assessments should:

- aim to develop metacognitive skills, not just content knowledge

- scaffold students through the assessment process, emphasising key stages like planning and review

- incorporate targeted guides to help students understand study skills

- connect to learning activities that allow students to practice these skills in low-stakes contexts

- use rubrics and feedback (including self- and peer-review) as educative tools to support metacognitive skill learning.

What does this mean in practice?

These principles provide us with direction around what we can do through assessments to foster student learning. We'd encourage you to find ways to incorporate some of these ideas into your own assessments, in ways that align with your own teaching philosophies. Our templates are a realisation of these principles making it easy for you to include them into your own tasks. As you continue expanding your teaching practices, we hope the inclusion of these principles into your assessments enables further learning for your students.

Category

Student Success

Hybrid Learning