News

Learning-centred rubrics in the age of AI

Share with colleagues

Download the full Case Study

Take an in-depth look at how educators have used Cadmus to better deliver assessments.

Why good assessment design matters more than ever

When generative AI entered higher education at scale, it triggered a familiar response: concern about misconduct, calls for better detection, and questions about how much automation is too much.

But for educators designing assessments day to day, a more practical question quickly followed:

If AI is now part of the assessment ecosystem, what foundations need to be strong first?

One answer consistently surfaces in both research and practice: marking rubrics.

Rubrics sit at the intersection of learning, assessment, and judgement. When they’re well designed, they support clarity, fairness, and learning. They also provide an opportunity to encourage rigorous academic writing and assessment processes.

Why rubrics still matter (and perhaps more now than ever)

Rubrics have long played an important role in higher education. They make expectations explicit, support consistency in marking, and help students understand what quality looks like. Well-designed rubrics improve transparency and reliability, particularly in large cohorts or when multiple markers are involved.

For students, rubrics also reduce uncertainty. When criteria and standards are clear, students are better able to plan their work, monitor their progress, and reflect on feedback. In this sense, rubrics are not just grading tools—they are learning tools.

The problem is that not all rubrics are designed this way.

Vague criteria, generic descriptors, or rubrics that aren’t clearly aligned to the task often leave students guessing and staff frustrated, potentially undermining learning.

Once AI enters the picture, these weaknesses are magnified. If students don’t understand what quality looks like, or why it matters, they may default to the fastest path to a polished submission.

What high-quality rubrics have in common

Across the literature, effective rubrics tend to share several characteristics. At their core, they make judgement visible and standards legible to students.

They are:

- clearly aligned with learning outcomes and disciplinary standards

- built around specific, observable criteria rather than abstract traits

- structured with meaningful performance levels that distinguish quality clearly

- analytic in nature, supporting consistency and reliability in marking

However, students often see rubrics primarily as grading instruments rather than as guides for learning, particularly when descriptors are ambiguous or overly general.

This highlights an important limitation: even good rubrics have limited impact if students only encounter them at the end of an assessment.

The value of rubrics increases significantly when criteria specific to the learning journey are integrated—encouraging drafting, feedback, revision, and self-evaluation along the way.

Using rubrics to assess writing processes and engagement

For much of higher education’s history, rubrics have been used primarily to evaluate final submissions. That still matters. But in an AI-enabled assessment landscape, the final product alone is no longer a reliable proxy for learning.

This is where many assessment designs are now evolving.

Enter process-driven assessment.

When we talk about process-driven assessment, we’re talking about assessments that are designed to make learning visible as it happens, not just at the point of final submission.

In practice, this means structuring tasks so students engage in meaningful stages: planning, researching, drafting, receiving feedback, revising, and reflecting. Each stage contributes to learning rather than acting as a hoop to jump through. The focus shifts from evaluating a single artefact to understanding how students develop ideas, make decisions, and respond to feedback over time.

This approach isn’t new. It draws on well-established research in writing pedagogy and formative assessment, which shows that learning deepens when students are supported through cycles of feedback and revision. What is new is the urgency. In an AI-rich context, where fluent text can be produced quickly, process-driven assessment helps ensure that assessment still captures thinking, judgement, and engagement.

Learning-centred rubrics play a critical role in this design. When rubrics are aligned to learning outcomes and embedded throughout the assessment process, they guide students as they work, not just explain a grade at the end. In this way, rubrics become tools for learning, feedback, and reflection on process.

Process-aware rubrics make expectations explicit around learning behaviours that experienced academics already value, including:

- sustained engagement across drafts and revisions

- meaningful use of feedback

- development of argument or voice over time

- reflective decision-making and justification

- appropriate and transparent use of generative AI

This does not mean lowering standards or replacing academic judgement with compliance metrics. It means articulating quality in relation to learning behaviours that actually matter. This is particularly important in disciplines where writing is a way of thinking, not just a way of reporting knowledge.

In an AI-rich context, this shift is critical. When fluent text can be generated quickly, assessment that focuses only on surface features risks rewarding efficiency over understanding. Rubrics that attend to process and engagement help re-centre assessment on the act of learning and make visible the intellectual work that AI cannot meaningfully perform on a student’s behalf.

When paired with assessment designs that surface drafts, checkpoints, feedback responses, and reflection, these rubrics support more defensible judgements about learning and send a clear message to students: how you work matters, not just what you submit.

Making process-driven assessment practical

AI hasn’t changed what good assessment looks like, but it has raised the stakes.

Clear learning outcomes, learning-centred rubrics, and thoughtful academic judgement still matter. What’s changed is the pressure to deliver these consistently, across large cohorts, with students using AI as part of their everyday study practices.

Most educators already know what good assessment looks like. The hard part is finding the time and the systems to do it well, consistently, and at scale.

Designing process-driven assessments takes care. Writing learning-centred rubrics takes intention. Supporting drafting, feedback, reflection, and appropriate AI use across a cohort is difficult to sustain without the right structures in place.

This is where Cadmus helps.

Cadmus brings assessment design, rubrics, drafting, feedback, reflection, and learning insights into one connected environment. Rubrics don’t sit at the end of a task - they guide students as they work. Students see criteria while drafting, use them during feedback and revision, and return to them when reflecting on their learning.

Drafts, checkpoints, and feedback are built into the assessment flow, making learning visible well before final submission. That visibility matters in an AI-rich context. When students are supported to engage with the process, the incentive to shortcut learning drops away.

Integrity is no longer something enforced after submission. It’s designed into the assessment itself through a proactive, preventative and educative approach.

For institutions, this approach scales. Instead of relying on individual academics to redesign assessment each semester, Cadmus supports consistent, learning-centred practice across courses and programs, while still preserving disciplinary nuance and academic judgement.

In the age of AI, the goal shouldn’t be tighter control over student work. It’s still just ensuring learning.

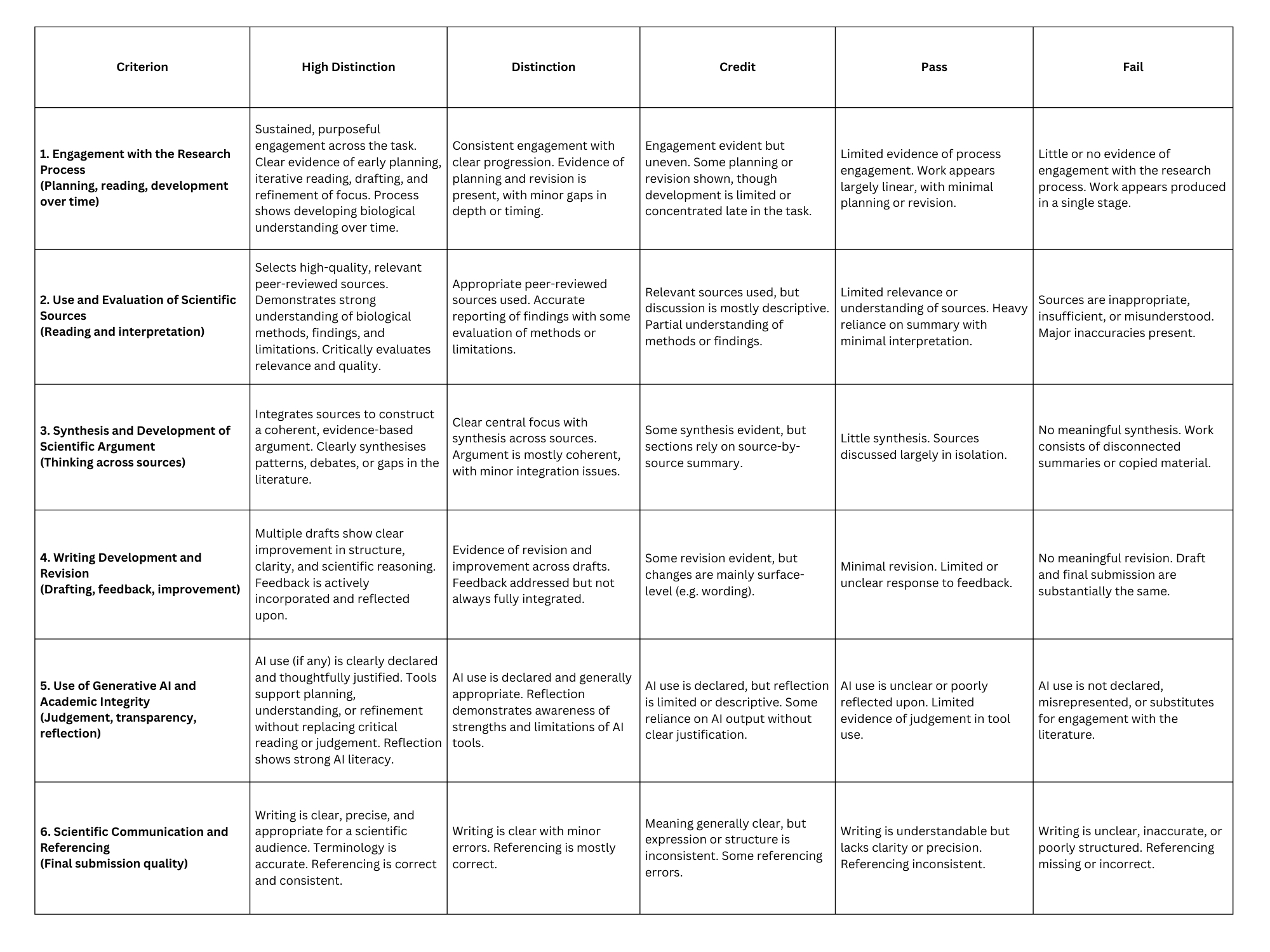

Below is an example of a process-aware, learning-centred rubric.

Process-aware, learning-centred rubric

Category

Teaching & Learning

Assessment Design

AI

More News

Load more

Academic Integrity

Assessment Design

Teaching & Learning

Student Success

From bold ideas to real assessment change: What we heard at the Universities Australia Solutions Summit

Last week in Canberra, the Universities Australia Solutions Summit delivered on its promise of big ideas, bold conversations, and real solutions. These are the themes that stood out—from keynote sessions to candid conversations with university leaders across the Summit.

Cadmus

2026-03-02

Assessment Design

Company

Independent ROI analysis: What the findings mean for Universities

Independent analysis by Nous Group confirms a clear link: stronger assessment design improves student outcomes, strengthens retention, and delivers measurable financial return — with a 7.1x average ROI.

2026-02-18

Assessment Design

Leadership

Teaching & Learning

Secure assessment: From policy to practice

This article examines how Australian universities can translate assessment policy intent into sustainable practice amid growing pressures from generative AI, regulatory expectations, and equity considerations. It advocates a shift from surveillance-driven approaches toward a whole-of-institution, design-led model of academic integrity that balances secure assessment with learner-centred practice and public trust.

Cadmus

2026-02-09